Modern philosophy – Britannica

Medieval philosophy - Britannica

Essay on the book: History of Philosophy: Medieval philosophy – Britannica

Essay on the book: Modern Philosophy – Britannica.

- At first, German idealism tried to go beyond what Kant had said about philosophy, but later, with the advent of positivism, utilitarianism, and other rational ideas, the importance of thinking about things beyond the physical diminished. This made science and the focus on real experience more important in the 20th century.

Introduction

Looking at the past allows us to better understand the present. Two centuries ago, the philosophies that prevailed in Europe began to transform to reflect the social, political and historical changes that were shaking the continent.

In Germany at the beginning of the 19th century, German idealism emerged as an idealist response to the limitations that Kant had imposed on human knowledge. Thinkers such as Hegel and Schelling set out to overcome Kantian dichotomies through a panoramic vision of reality based on reason. For them, reason should not only guide the natural sciences, but was also capable of apprehending being itself through absolute knowledge. However, its metaphysical claims were criticized by those who preferred an empiricist approach.

Meanwhile, in Paris in the 1830s, Auguste Comte argued that mathematics and the natural sciences had become the pinnacle of human thought. Inspired by the scientific method, Comte founded positivism as a program that opposed the use of speculative reason. For him, philosophy should be limited to the study of observable phenomena, stripping itself of all metaphysical pretensions.

In England, the philosophies of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill demonstrated how a nation could prosper by applying rational principles of utility and progress. Meanwhile, the socialist and materialist doctrines of Karl Marx anticipated a paradigm shift that would shake the world over the next century.

To make sense of this effervescence of ideas, this essay will explore how three philosophical currents that successively dominated the 19th century—German idealism, French positivism, and English utilitarianism—reflected Europe’s complex transition toward modernity.

German idealism

German idealism marked a turning point in the philosophical thought of the 19th century. Following Kant’s critical philosophy, thinkers such as Hegel and Schelling set out to go beyond the limits imposed by their predecessor.

For Hegel, the limitations on knowledge established by Kant meant a scandal. While Kant warned us about the risks of speculative metaphysics, Hegel fervently believed in the ability of reason to achieve an absolute understanding of reality. “My thoughts are the thoughts of God before the creation of the world,” he boldly declared in his Science of Logic. Hegel attempted to transcend Kantian antinomies through a holistic vision of the world as a rational totality.

However, following Hegel’s intricate reasoning was a daunting task even for his own students. As one of them recalled, “I spent three hours sitting in front of Hegel’s logic, trying to understand it; in the end my head hurt so much that I had to throw the book against the wall.” Schelling, for his part, proposed a more accessible Naturphilosophie (philosophy of nature), although no less ambitious in its metaphysical pretensions.

Meanwhile, idealistic speculations faced the growing relevance of the empirical sciences. In anatomy, microbiology and other medical fields, discoveries occurred at a dizzying pace. This intellectual climate encouraged the emergence of French positivism, which rejected metaphysics in favor of the scientific method. The increasing influence of the natural sciences would undermine the foundations of idealistic pantheism in the following decades.

However, the audacity of thinkers like Hegel contributed to renewed interest in eternal problems such as human freedom, whose complexity became evident in the face of the omnipresent tyranny of natural laws. Although idealism failed in its claims to absolute knowledge, it helped lay the foundation for debates that continue to this day.

The rise of rationalism

The upsurge of positivism in 19th-century French philosophy represented renewed inspiration from Anglo-Saxon empiricism. Figures like Auguste Comte led a movement that rejected the excessive metaphysical pretensions of thinkers like Hegel.

For Comte, German idealism lacked scientific rigor. His extravagant theories of absolute knowledge had little to do with observable reality. In their desire to transcend the laws of nature, idealists strayed dangerously far from the humble task of understanding the world as it is. As he declared in his Cours de philosophie positive, “the time of metaphors is over; the time of facts has arrived.”

After centuries of metaphysical ramblings, Comte believed that humanity had come of age. The sciences had reached a level of maturity that allowed them to aspire to understand social phenomena with the same precision that Newtonian physics had achieved with the physical universe. The positivists set out to build a new philosophy based on the scientific method, which placed observation and experimentation at the center of their work.

However, some found this approach overly restrictive. Science could illuminate the domains of the physical and the biological, but what about the ethical and the aesthetic, also constitutive of our human condition? The mere description of the phenomena was not enough to satisfy the deepest questions about the destiny of humanity. At the same time as the rise of the natural sciences, currents emerged that defended the irreplaceable role of imagination and spiritual values.

Positivism represented a paradigm shift in the ways of understanding knowledge. However, in his radical skepticism towards the transcendental, he perhaps lost sight of essential aspects of the human condition that would later be recognized as fundamental. In the complex transformations of the 19th century, scientific reason did not exhaust all the richness of humanity.

Irrationalism and Materialism

Irrationalism and materialism marked the philosophical debate of the 19th century with a strong critical charge.

While German idealists postulated an omniscient reason, thinkers such as Schopenhauer vindicated the role of irrational forces in human existence. In The World as Will and Representation, Schopenhauer presented a pessimistic vision of the world dominated by suffering. “Life swings like a pendulum between pain and boredom,” he declared listlessly.

Schopenhauer never knew his father; perhaps this biographical background influenced his emphasis on instinct over reason. Just as we are driven by hunger when we have an appetite, he argued, our actions respond to unconscious forces rather than rational calculations. This anticipatory defense of the unconscious had enormous impact on later thinkers such as Nietzsche and Freud.

Other currents, such as Marx’s dialectical materialism, challenged idealist supremacism by appealing to more tangible experience. For Marx, it was not omniscient reason but the dialectic of social classes that drove the march of history.

However, the prevailing intellectual climate was still dominated by Hegel’s muses. So bolder thinkers like Feuerbach opted for subtle ways to subvert the status quo. In The Essence of Christianity, Feuerbach argued that God is only a projected reflection of human aspirations.

These philosophical heresies prefigured debates that continue to this day, questioning the limits of reason and claiming the emergence of the unconscious in human existence.

Conclusion

The philosophical debate of the 19th and 20th centuries revealed the eternal tension between reason and passion.

Throughout this essay we have explored how this struggle permeated all the debates of the time. On the one hand, the German idealists opted for a totalizing reason, capable of understanding the totality of being. While thinkers like Schopenhauer claimed the catalytic role of unconscious forces.

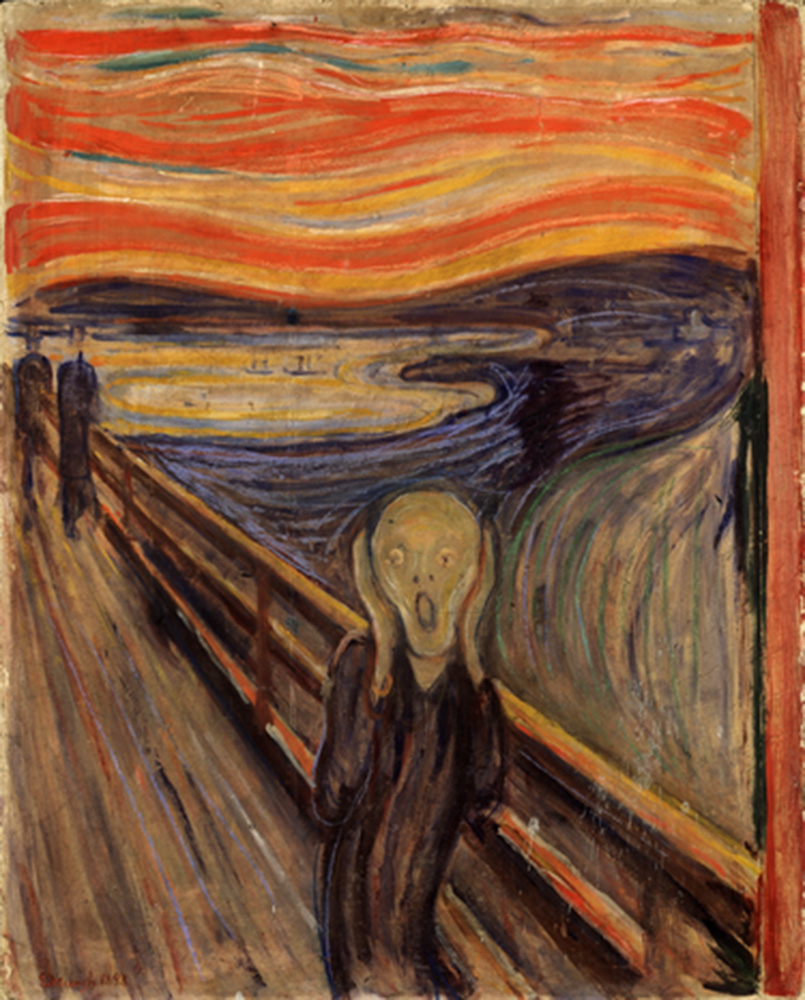

It is not surprising that this philosophical discord found its reflection in a turbulent world, marked by industrial and political revolutions. Scientific reason promoted material progress, but apparently left aside other dimensions of our being.

Perhaps the most important lesson is to recognize that both reason and passion are part of our human condition. Trying to exclude one or the other would lead us to nonsense, since both shape our presence in the world.

It is true that reason illuminates great works of civilization. But it is also true that art and religion have provided meaning to countless lives. It would be petty to reduce existence to mere logic.

Instead of opposing concepts, perhaps what is fruitful lies in overcoming dichotomies. After all, as Freud pointed out, not even the conscious mind escapes the influence of the unconscious. Both strata make up the complexity of humanity.

Thus, despite the diversity of approaches, all these thinkers agreed on one certainty: that understanding ourselves constitutes one of the most exciting projects in history. For this reason, his philosophical legacy endures today as an enduring stimulus for reflection.

0 comments