Medieval philosophy – Britannica

Medieval philosophy - Britannica

Essay on the book: History of Philosophy: Medieval philosophy – Britannica

Essay on the book: Medieval Philosophy – Britannica.

- Medieval scholasticism represented the successful effort to integrate the Christian and classical intellectual legacy with the new philosophical ideas introduced, particularly the thought of Aristotle, laying the foundations for the later development of Christian thought and other fields.

Introduction

Can you imagine a world without the Internet? Today, it is almost impossible for us to conceive of our daily lives without the Internet. However, just a few centuries ago the situation was very different. People communicated by letters that took weeks to reach their destination, and access to knowledge was restricted to a select group of scholars. It was in this context that a philosophical movement emerged that would transform the intellectual landscape of the time: medieval scholasticism.

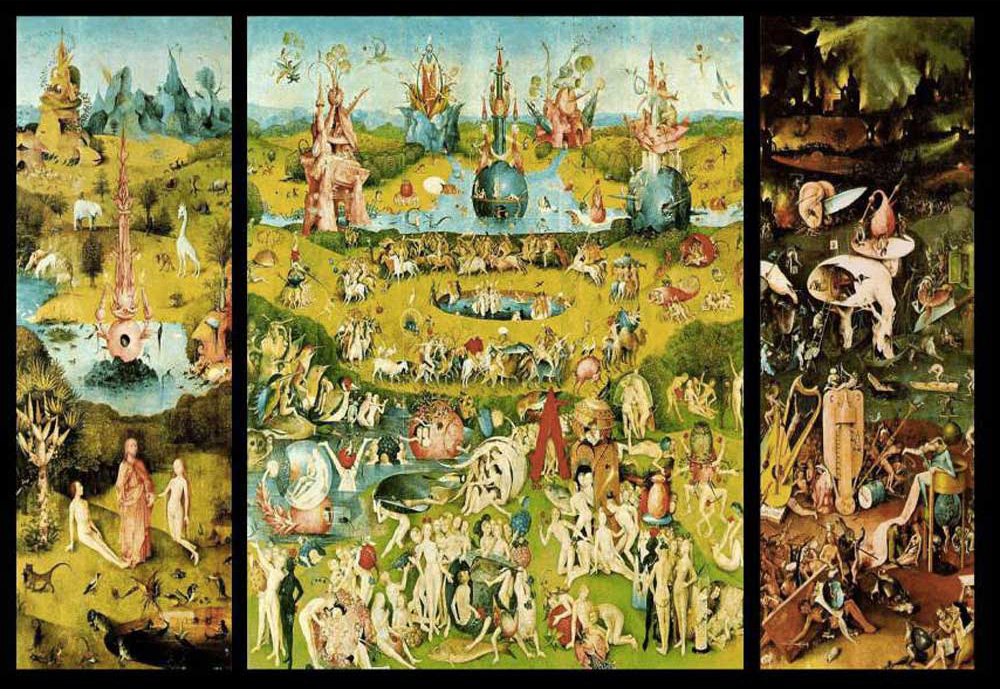

As European nations emerged from the fall of the Roman Empire, the Catholic Church emerged as the mainstay of culture and education. Monasteries became centers of study where monks like al-Andalus translated philosophical works from Greek and Arabic into Latin. In this way, Europe had access for the first time to authors such as Aristotle, unleashing a torrent of new ideas that clashed with the prevailing theological vision. It was in this context of change that a movement arose that attempted to synthesize the rich Christian intellectual legacy with the newly arrived philosophical currents: scholasticism.

To better understand this stormy era, let us consider how the advent of the Internet profoundly altered the way we relate to one another. In the same way, scholasticism sought to harmonize two languages – that of faith and that of reason – which until then had followed separate paths. This endeavor gave rise to sharp disputes in which figures such as St. Thomas Aquinas, who masterfully spun seemingly contradictory concepts, stood out. Their success in laying the foundations for compatibility between theology and other disciplines marked the beginning of the late Middle Ages, when science finally emerged from the shadows.

A curious fact that illustrates the intellectual revolution that took place is that while in 12th century Europe there were barely a dozen universities, by 1300 their number had multiplied sixfold. This proliferation reflects the rise of the scholastic method, whose legacy lives on today through values such as the critical spirit and dialogue between traditions.

THE INITIAL CHALLENGES OF SCHOLASTICISM

In its beginnings, scholasticism had to face an overwhelming amount of knowledge inherited from the classical and patristic eras that needed to be systematized and transmitted to new generations. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, Western culture was dispersed, preserved in a fragmented form in the libraries of European monasteries.

The monks, who assumed the role of guardians of the tradition, devoted themselves to the arduous task of tirelessly compiling and copying the manuscripts that made up the intellectual heritage of the past. However, the magnitude of this legacy was overwhelming even for capable monastic minds. At the same time, the emergence of new currents of thought from the Arab world represented a major challenge for Christianity.

In that context of tribulations, an ordinary citizen might well have felt overwhelmed by the avalanche of knowledge that threatened to annihilate all certainty. Nevertheless, figures such as Albertus Magnus emerged who, moved by an innate inquisitive spirit, dedicated their lives to the enormous task of mapping the inherited universe of conceptions.

One of Albert’s crucial contributions lay in his conviction to study nature through direct observation, beyond the mere recapitulation of texts. Thanks to this, he laid the foundations for disciplines such as botany, zoology and other natural sciences to find a place within Christianity. However, the recovery of the ancient philosophical legacy presented another difficulty: how to integrate Aristotelian discoveries about the physical cosmos with the revealed truths of faith?

ARISTOTELIAN THOUGHT REPRESENTED A CHALLENGE TO SCHOLASTICISM.

After centuries of lethargy, Aristotle’s philosophy suddenly emerged when his treatises were translated from Greek and Arabic into Latin. While the study of logic was already commonplace in universities, thanks to the writings of Boethius, scholasticism was now faced with a masterpiece that covered all fields of knowledge.

For many thinkers, the empiricist and rational impetus of this new corpus clashed head-on with the revealed truths of faith. Institutions such as the University of Paris even forbade the study of works such as Aristotle’s Physics. However, for inquisitive minds like Albert the Great, the Stagirite possessed keys capable of revealing the secrets of the cosmos.

Alberto set himself the colossal task of deciphering Greek syllogisms in the light of Latin. Such was the difficulty of the undertaking that, in a fit of passion, he used to say: “Oh, if only I knew Greek! Then I could drink directly from the fountain of wisdom”.

Not content with translating, Albert dared to articulate Aristotelian thought with Christian theology. For him, the careful observation of nature constituted a legitimate way of approaching the divine. In the same way, he conceived philosophy as a vehicle capable of unraveling the unfathomable truths of faith.

However, accepting the intellectual baggage of the Stagirite entailed difficulties, as Albert himself recognized. After reading the writings on the physical cosmos, he found himself perplexed by conceptions such as the eternity of the universe, as opposed to the doctrine of creation.

Years later, another genius, St. Thomas, appropriated the Albertine trail to lay the foundations of a fruitful synthesis between the Aristotelian tradition and revelation. His mark would last for centuries, although his philosophical advances did not always meet with ecclesiastical approval.

THE MATURITY OF HIGH SCHOLASTICISM.

Led by brilliant minds like St. Thomas Aquinas, scholasticism reached its golden age. Thomas, a Dominican monk with a passion for Aristotle, undertook nothing less than the titanic task of harmonizing Christian theology with the philosophy of the Stagirite.

In his famous work Summa Theologiae, the saint meticulously dissected every aspect of Christian dogma. His writings astonished the world with their conceptual clarity and perfectly supported philosophical system. However, the road was not easy for the friar who became a saint.

As Thomas Aquinas once said, “If only I knew Greek!” Understanding the language of Plato and Aristotle was quite a feat. And beyond language, controversies such as the eternity of the universe or the existence of God arose.

Nevertheless, Aquinas’ sharp mind masterfully deciphered every Gordian knot. Concepts such as the distinction between essence and existence, the creation of the world from nothing or the rational soul of the human being gained solid foundations.

Other geniuses such as Albertus Magnus and Bonaventure of Fidanza also made lasting contributions. However, the stamp of Aquinas forever impregnated scholasticism, whose rethinking of Aristotelianism built the foundations of European thought.

After the zenith of Thomism, philosophy acquired greater autonomy from the hand of dissident thinkers. Among them, the acute Juan Duns Scotus, who qualified the Thomistic thesis on divine simplicity, stands out. On the other hand, the German William of Ockham contributed new readings on nominalism.

This explosion of ideas greatly enriched the philosophical debate. However, it also heralded the gradual decline of a method that, after five centuries of constant elaboration, progressively exhausted its power of renewal.

CONCLUSION

Over the centuries, scholasticism forged a rich and profound thought. Figures such as Albert the Great and St. Thomas Aquinas unveiled philosophical wonders whose lineage endures today.

The legacy of these sages permeates our culture in countless ways. By expounding the truths of the faith with a passionate dialectic, they brought theology closer to those who yearn to understand the divine mystery with their minds.

They also highlighted the value of investigating the cosmos through experience and reasoning. In this way, they paved the way for modern science and invite us to admire the creative work of the Creator.

Even so, all philosophy has an expiration date. For this reason, scholasticism languished when it exhausted its renewing dynamism. However, its robust roots still nourish the fertile soil where our path germinates.

Undoubtedly, the debate between faith and reason is constantly evolving. New questions about God, the soul and the future of the universe will arise in every age. Nevertheless, the seed planted by the great masters bears fruit that is always seasoned.

Thus, although the scholastic method has come to an end, the search for a balance between revelation and understanding remains in full force today. For the attempt to feed mind and spirit constitutes an eternal beat of the human heart.

Thus, with optimism, we can affirm that the legacy of scholasticism will continue to nourish the philosophical endeavor as long as man’s curiosity for the transcendent and the need to harmonize reason and faith persist.

0 comments