The Denial of Death

The Denial of Death

Essay about the book: The Denial of Death

ESSAY ON THE DENIAL OF DEATH

- Kierkegaard anticipates fundamental concepts of modern psychology around the development of human character as a defensive way of denying the existential condition of the human being (Death).

Introduction

Anticipating ideas now recognized, Søren Kierkegaard awakened our capacity for introspection in his time. Nearly two centuries ago, he suggested that facing our fears is key to flourishing as individuals.

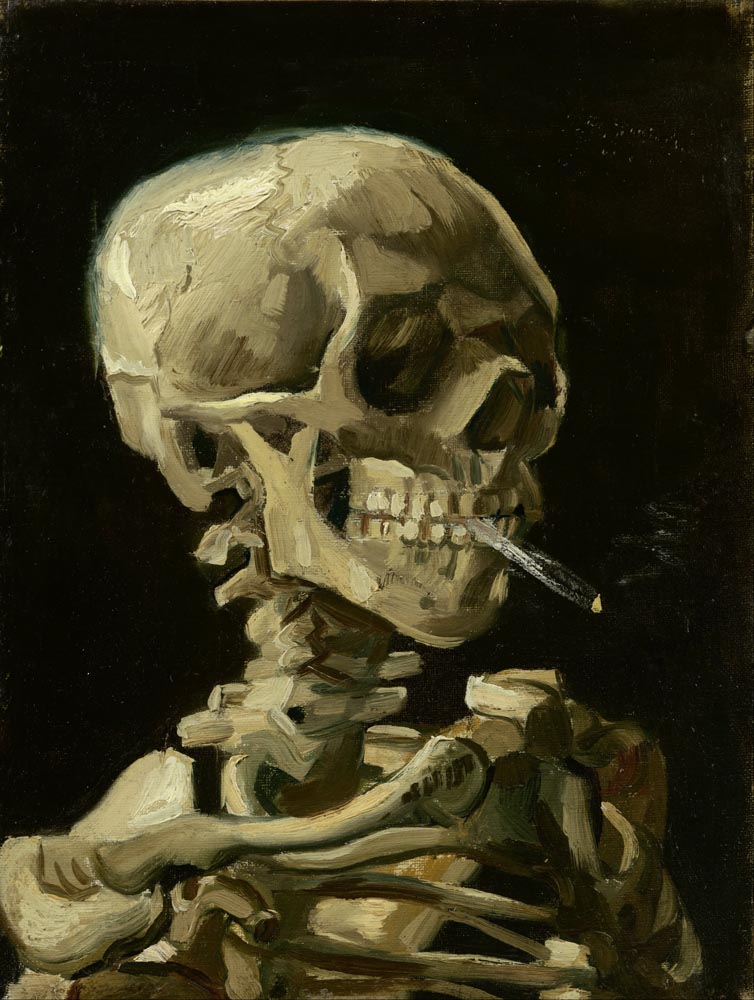

For Kierkegaard, our deepest fear is of death, which is born of knowing our finiteness. More than corporeal beings, he fears that we are thinking consciousness trapped in bodies. This dualism generates ontological anxiety that we avoid through rationalizations. The Dane suggests that repressing such consciousness alienates us, depriving us of authenticity.

However, he intuited that accepting our paradoxical essence is liberating. This insight anticipated current debates in the humanities and behavioral sciences. With surprising acuity, Kierkegaard confronted our tendency to confine ourselves to preset roles. He highlighted how personalities are molded in childhood to elude existential angst. However, he proposed that by taking ourselves on we elevate ourselves. How do we achieve such a goal without falling apart? This enigma has provoked reflection since the Greeks.

In this essay we will explore Kierkegaard’s early insight into the mechanisms of the mind. We will address his classification of character and pathological states. We will also contrast his vision of the SELF with later approaches. Finally, we will investigate what his invitation to introspection brings us today, in a world where fear proliferates more than consciousness.

THE EXISTENTIAL PARADOX

The existential paradox in the human being has generated reflections throughout history. Since the Greeks, our duality between flesh and spirit has been debated. Søren Kierkegaard addressed this apparent dichotomy with surprising acuity in the 19th century.

For Kierkegaard, what differentiates human beings from other animals is our self-consciousness. While other creatures act guided by instinct, we can reflect on ourselves and our environment. However, like them, we are bound to a finite body. This duality generates ontological reflections that the Dane knew how to relate to anxiety.

Our dual condition confronts a spiritual freedom with a bodily determination. We are thinking beings caged in perishable flesh. This contradiction lies in the fact that our essence transcends the material. Yet we are dependent on a mortal sheath that reminds us of our finitude. Kierkegaard suggests that repressing such a contradiction is the source of our ills.

In analyzing the biblical myth of Genesis, Kierkegaard intuited the paradoxical nature of the human. He identified the knowledge of good and evil as the moment when we acquire self-consciousness and, therefore, anxiety. This discovery places us between animal innocence and angelic transcendence, according to his perspective.

Rather than seeing in myth a literal story, Kierkegaard glimpsed an allegory of the existential condition. He understood that our ontological duality is inherent in the emergence of reflection. In acquiring consciousness, the human being faces the paradox of his own divided nature.

DEFENSIVE DEVELOPMENT

The existential paradox generates anxiety in human beings. To deal with this uncertainty, we develop unconscious defense mechanisms known as “character”.

From an early age, we face the duality between spiritual freedom and bodily determinism. This contradiction reminds us of our finitude, awakening fear of vulnerability and death. Faced with such a dilemma, the child models attitudes to manage distress.

Thus, we unconsciously create a personality that protects us from fear. At first, our defenses are spontaneous and playful. Over time, however, they become integrated into more rigid, unconscious patterns. Instinctively, we mold a mask that simulates control over uncertainty.

For example, we tend to externalize anxiety through mechanisms such as aggression, hyperactivity or perfectionism. Similarly, we project guilt onto others in order to feel safe. We may even repress painful emotions for fear of losing self-control. Either way, we forge armors that sustain an illusion of mastery.

However, character also provides adaptive benefits. It allows us to operate in the world automatically, freeing resources for other tasks. It also endows us with identity and predictability in social relationships. However, this apparent strength masks a fragile inner vulnerability. Our personality is actually a defensive prison.

Years later, when anxiety re-emerges, we can no longer respond spontaneously. Trapped in rigid frameworks, we only repeat mechanisms that are not very flexible and independent. But character, despite its usefulness, distances us from our most authentic self.

CHARACTER AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

Character models different styles of approaching life. Kierkegaard described some patterns that illustrate human psychopathology.

One form is the aesthete, who seeks frivolous pleasures to hide anxieties. However, lacking spiritual purpose, his happiness is hollow. In favor of amusement, he squanders his existence without transcendence.

There are also hypochondriacs, who blame their unhappiness on physical trifles. They imagine deterioration to justify their inaction, feeling that they are victims of grievances. In this way, they shift the blame for their boredom to other people’s circumstances, avoiding self-examination.

Then there are the cynics. They pride themselves on their cynicism, arrogance and skepticism. With paid airs and graces of superiority, they despise faith and ideals. But their apparent strength hides fear of the vulnerability inherent in human beings.

No less common are depressives. They feel unhappiness without apparent cause, unable to enjoy life. Trapped in perpetual complaints, they find no meaning in existence. Their pessimism does not stem from reason, but from fear of the responsibility of freedom.

These nuances reflect ways of evading the challenge of existence through denial. By repressing the underlying anxiety, the psyche fragments into irrational symptoms and patterns. However, facing the truth about oneself is the step toward integration.

Indeed, human beings can only achieve personal fulfillment by courageously assuming their dual nature. Otherwise, he will remain a prisoner of inauthentic roles. The key is to accept our paradoxical condition with humility and courage.

HUMAN SELF-INVENTION: A COMPARATIVE VIEW

Kierkegaard and Maslow agreed on the need for the individual to construct his own existence. However, they differed subtly in the emphasis of this creative process.

For Kierkegaard, self-invention implies assuming the freedom and responsibility that comes with our paradoxical condition. It means recognizing that we lack a pre-established essence, and embracing our capacity to choose our own actions. This exercise takes place in solitude and represents an act of courage.

Maslow, on the other hand, emphasizes the potential for introspection and personal development of each individual. He promotes self-realization through self-mastery and the continuous stimulation of inner growth. He conceives self-invention as a natural process of expansion of innate capacities.

Both conceive of the human being as an unfinished project. However, Kierkegaard places greater emphasis on the sacrifices involved in freedom and maturity; he highlights the existential anguish generated by being alone in the face of the abyss of one’s own decisions. His perspective is more demanding as he confronts our tragic condition head-on.

In light of the above, self-invention for Kierkegaard is a very difficult task, a challenge that pushes us beyond our limits. Maslow, on the other hand, offers a more optimistic view, focusing on the potential inherent in every human being. However, he avoids in part the struggles and conflicts involved in facing oneself.

In short, both visions are complementary and enriching for understanding the paradoxical nature of the human condition. Maslow’s introspection nourishes the agonizing Kierkegaardian enterprise to achieve true individuality.

CONCLUSION: THE HUMAN CONDITION

Throughout this essay we have explored the paradoxical nature of the human being, analyzing the origins of defensive character development and the various nuances of psychopathology. This journey has allowed us to discover the individual’s tireless quest to cope with his existential condition.

As Kierkegaard observed, man emerges into a world loaded with meanings that he does not understand. He lacks a pre-established essence and is forced to choose his own destiny in solitude. Embarking on this path implies assuming an overwhelming freedom and the responsibility that comes with our dual nature (flesh and spirit).

To evade the anguish of this paradox, the child develops “neurotizing” defenses that become the armor of his personality. However, this concealing screen ends up trapping the individual in a self-imposed captivity. Only by courageously facing his vulnerability can he aspire to transcend himself.

Even so, genuine personal growth demands a titanic effort. It means facing the impossibility of controlling the precariousness of destiny, as well as the limits of our mortal flesh. Only the most intrepid spirits achieve this feat, as the Danish philosopher emphasized in his prose.

Nevertheless, we must not give up. Even if man never achieves the answers he longs for, his tragic condition does not exempt him from continuing to strive for a valued and meaningful existence. In this unfinished enterprise lies the breath of the human adventure on Earth. This battle is worth living.

0 comments